toby creswell revisited: the jeff buckley interview

Grace Under Fire:

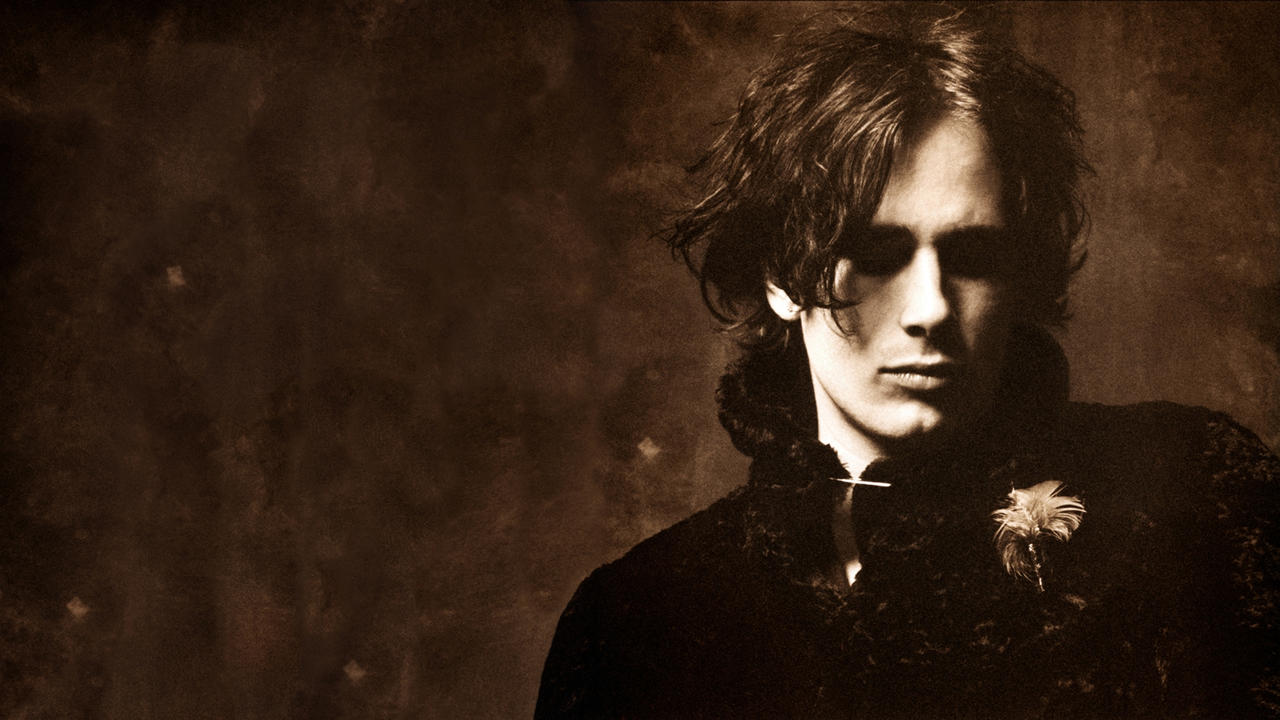

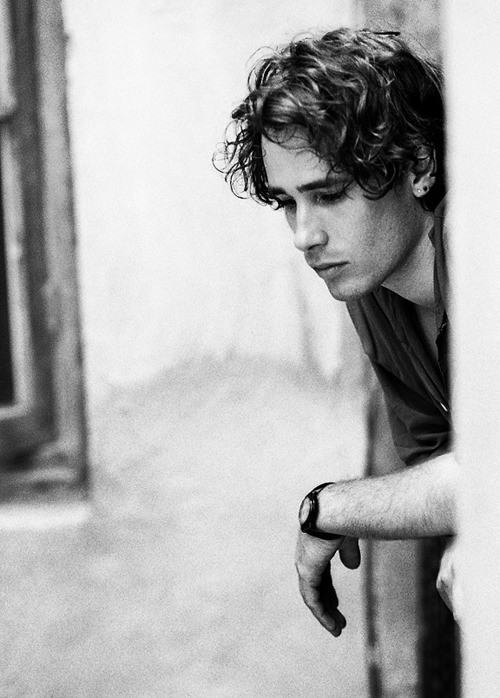

On the eve of his second Australian show, Jeff Buckley reflects on words and music, fame, sex and what it takes. Toby Creswell hears confession….

“The record is fantastic, you and I know that. The band is really great and, let’s face it, all the women want to get into his pants.” This is how a record company person described Jeff Buckley to me last year, suggesting that perhaps Buckley would make a good cover forJuice. Although we didn’t go with the suggestion, the analysis is fairly accurate. Buckley’s debut album Grace is one of the most passionate and intriguing releases of recent years, the band is great and Buckley has the looks and the charisma to make him a star. Columbia Records brought Buckley out for a showcase gig last year and ticket sales went berserk; new shows were added and a theatre tour booked and put on sale without the benefit of hype or hit singles. Jeff Buckley has the hallmarks of a phenomenon.

It hasn’t been an overnight rise however. Buckley has been playing music for most of his life. In 1991 he was invited to perform at a New York tribute show to his late father Tim, and his talent started to attract notice. Then it was another few years playing downtown clubs and the recording of his Live at Sin-é mini-album before Buckley was really taken very seriously. Once the deal with Columbia was signed, Buckley then quickly put together the musicians for the record. His intent was to look for spirit and imagination in equal parts to the musicianship. His band was mostly New York buddies, guitarist Michael Tighe, bass player Mick Grondahl and drummer Matt Johnson. “I got signed before I got my band,” said Buckley. “Rather than have anybody pick my band, I decided to stall until I found the right people. So I stalled and I lied. Nothing was really happening, because I hadn’t found anybody. So finally Mickey walked up to me and he said he was interested in playing. We went back to my place about two in the morning and bang, he was the one, boom. Then Matty. The first time we go together, we got the music for “Dream Brother.” He didn’t even know who the hell I was. And boom, there it was. So we had the trio and we recordedGrace.

“I’d always known Michael throughout that whole time, daydreaming of having Michael in the band. Michael was primarily an actor before, because he was on the downtown theatre scene, avant garde, ever since he was 12, just acting in people’s plays and shows and stuff. Then around the time he was 16, he just picked up the guitar for a play. He actually just picked up the guitar to do in a play, and he just found that he liked it a lot. Soon as you pick up a guitar, you just tap into this whole black rock of culture of guitar players like from Son House to Muddy Waters. Those are the people he totally fell in love with - Mississippi John Hurt, Howlin’ Wolf and Robert Johnson.

“When we met, we immediately bonded on those things. But he had never been in a band before, and hadn’t even been in a garage band, or anything. He’d just gotten together with directors in plays. So he had a very, very different idea about music - very different. The first time he picked up my guitar, he played the music to “So Real.” It was disjointed and it wasn’t together, and it wasn’t anything. Those are his tendencies, right there. Those are his… Everything about his style is right there. I made it a song. If I didn’t come along, it would have just been a blob.

“So one day, during the auditions for the fourth member, I always had him in the back of my mind. So I auditioned about nine guitar players, and he was the ninth. He was very scared and he didn’t even have a proper cord; he had a cord about a foot long, and the strap didn’t work, so he had to sit down and the jack was jiggling, hanging out like a torn out eye socket. The rest of the guys that we auditioned had a lot of effects and they held their chops together and were proficient players, but he had a rhythmic sense that sent us into a whole new thing. That’s how I knew that he was the fourth guy.”

The songs that made up Grace were assembled from Buckley’s catalogue with some choice covers (Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” and Nina Simone’s “Lilac Wine”). “I just thought it should link this album to my past a little,” he said at the time. “Grace is like…a lot of this stuff … I don’t know how to describe it to you…It’s just a bunch of things about my life that I wanted to put in a coffin and bury forever so I could get on with things.

“The ones that we made - “Dream Brother,” “So Real,” “Last Goodbye” and “Eternal Life” - mean a lot to me because at the time that I wrote them, a long time ago, I was around an environment that thought that they were completely loser songs. It was rotting away. I put them on the album to prove at least to the songs that they weren’t losers. They were worth recording. Sort of like finding kids that have been told all their lives that they’re pieces of shit, and finally you have to go around proving to them, by putting them in a completely other setting, that no, they are worth knowing and loving.

“So those mean a lot to me. And “Grace” and “Mojo Pin” because of what the guys did to them. They fleshed it out Mickey and Matt. I love “So Real” because it’s the actual quartet that you see in that picture right there that you have on the wall, on the album. And that one I produced live all one moment, the vocal is the first take, all one take. It was three o’clock in the morning.”

One key to Grace is its intimacy, from the almost barely breathed vocal parts in some songs to the violent gnashing of guitars which are no less violent for the restraint in volume. It’s short on multi-tracked bombast but long on hard truths.

According to Buckley: “ The thing is that I also like to have lyrics that are inclusive, that give you space to be inside them, to put your experience on to them, so that they can move through moments. There’s a way of writing where you just include all the streets around your house and all the people you meet. You actually name them autobiographically in the song. Well, that song is very hard to travel through time. It may not last in its meaning. It may not touch every time because those people and events fade away and they may mean something to your life and your understanding of that life. I like things to be more universal. It’s a balance between… Obviously it’s got to grab some skin from me. I like the way that songs sort of have light, and sort of travel around despite you. It’s good. It helps to have songs that you love, that you can be inside. It’s good. It’s part of the invention. On the outside of that you can say that I find great joy in the things that are sad. That’s the way emotions are in people. They fall down on you and there’s no way to get out, except to go through it. There’s no way you can control it, there’s no essay you can write to answer yourself out of it. It just soaks you like the rain. There’s nothing you can do. Then it’s gone and then another comes around. But tears are not all I deal with. I’ll leave that to the next album.”

The link with the songs is much like Buckley’s own attitude towards music and his heroes.

Juice: The kind of people whose songs you’ve covered from Leonard Cohen to Alex Chilton to Nina Simone are people who have a very fragile muse to them. They are people whose personalities have often been destroyed by their art.

Buckley: I think that fragility isn’t quite as accurate as sympathy, which takes a huge pain threshold. Some people are just born into bodies, born into lifespans that just don’t fit anywhere else and they have very little to hang onto to validate and also it’s a very lonely thing to notice a certain sense of life and be able to relate that to anyone. It’s probably the onset of madness, or it must seem so to the person who has it at the time, who sees the world in a certain way and it usually has a lot of real meaning. Maybe they see spirits everywhere or maybe they divine information from certain happenings and certain peoples that are invisible to most of us, and as a result people deem those experiences not valid and not important, and crazy too, and that can damage a person. Those characters you named have a lot of strength to them even though…There’s a lot of strength to the self-destructive soul. Not that it’s wise to be self-destructive, but it is wise.

J: The consequences of their art have led to their doom in a way, butyou appear bullet proof.

B: I’m not anything like that. I’m on the rapids. I see the waterfall ahead. I know I’ll fall. I scream. It’s never a result of the art form, but there’s something about the social life of a musician who lives as a musician and nothing else. It will bring you into the underground. Even in little shades, like if you’re a kid playing in a little bar you get to see bar life and people acting in that capacity as opposed to a school or a workplace, and anything goes there. There’s not a lot of security except for the stuff you have on your own.

J: Is it fun? Is it exciting?

B: There’s fun parts about it, there are parts about it that are totally indelible magic and there are bits of it that will make you want to eat your own flesh. It’s all hard. It’s all the same pressure and intensity. Even the boredom.

At twenty-eight years of age Jeff Buckley is very much a product of his times; his songs have the jagged worldweariness of the best ‘complaint rock’ lyricists like Billy Corgan or Eddie Vedder and his band has that stripped-down, deconstructed sound. However, in an art form that is increasingly divided by a generation gap, there is a thread that links him to the artists whose songs he covers, like Cohen, John Cale and Alex Chilton. The sum of those influences is a songwriter who is very much his own man.

As Buckley put in a Japanese fanzine, “I’ll always be a slobbering idiot for people I love: The Grifters, Patti Smith, the new Ginsberg boxed set, MC5 totally pulled out that one. I listen to Sun Ra. I listen to Kiss. Anything. Led Zeppelin. Bad Brains. Shudder to Think. Tom Waits. Lou Reed. De Niro.

“And Dylan. People who have had an actual life, have come through flame after flame, either on their own flame, or other flames of people hating them, or completely elevating them to god status, and them still being around. The last two things Dylan did are great. He is beautiful still. I appreciate that, and I’m happy. He hasn’t lost any of his…shock.”

As to the other thing, the sex thing, well, we talked about that.

J: You’ve got a reputation for being attractive to girls.

B: Oh no. Girls want me to sign things.

J: That’s the extent of it?

B: That’s not always the extent of it. There’s a certain type of character that will come up to somebody in a band and propose sex, right off the bat, and I really haven’t met one yet. There was this person who sent a letter to me in London saying how lonely she was and that she was attractive and would I please have sex with her. I think she was married. Because the letter so astounded me, I had to call this woman up and say whatever came to mind like, “I’m sorry I can’t have sex with you, but…” Believe me, at that time I was not in the mood for something like that. I called her up and I said, “Hey, it’s Buckley, Jeff…you know you wrote the letter.” And she says, “Oh I don’t want to talk to you right now.” And she hung up the phone. I don’t know. It’s because…Talk to the guys in Oasis about getting chicks because it’s very different for a band like this. We’re sort of there to play and there could be lots of coolness and adventures along the way but it’s not like hordes of women are after me at all.

J: I imagine you get the types who read poetry?

B: Lots of people send poetry. Lots of people are poets. Everybody’s a poet.

J: Yeah. I think it’s kinda unfortunate myself. Do you read poetry?

B: I read very few things. The stuff I do read is not dense at all, believe me. Like Rimbaud is very appealing to me, just the way it reads and how utterly shocking it is sometimes, thinking about who he was. Also poetry is supposed to have lots of metre and rhyme and stuff like that, but I prefer it to have more crazy shapes, like Ginsberg or good prose. I’m terribly interested in writing…I mean reading it. Just recently I started Cities of the Red Night [Burroughs] and at the same time a Noam Chomsky book, Lies and Democracy, but he’s easy to read and great to listen to.

J: I think it’s depressing that they’re making a Hollywood movie out of the life of Rimbaud with Leonardo DiCaprio.

B: That thing? It’s typical. I’ve ceased to be depressed by anything that comes out in the major media eye. It all pretty much sucks.

J: Things can lose their dark mystery if you expose them too much

B: Yeah. It would take a really vibrant, sympathetic and sick mind to pull of that story in a movie setting and not pull punches…I haven’t seen it, I’ve heard reports. I don’t know, I’ll see it sometime maybe in a hotel or on a plane. I head the same thing happened with DiCaprio and The Basketball Diaries very lame, but this is second hand. I really don’t care to go and see the movies. It is depressing. It’s depressing to go into a movie and know you’ll have all your buttons pushed rather than being taken through a really compelling story and really being transported to another place. Usually it’s all things that play on our fears or disgust or makes us very aware of ourselves. It’s a real test of romanticism that is missing from most things I see. Did you see The Addiction, the new film from Abel Ferrara? No? It’s yet another vampire movie, but it’s vampirism as an allegory for the Nazis and also for high society. [Laughs] The theme or the motif is that people are victimised by vampires only because they don’t resist evil. Time and time again in the movie the evil one comes up to the victim and says “I just want you to tell me to go away like you really mean it.” And they always say, “Please, please don’t hurt me,” and that’s when they get their necks chopped off. You’ve gotta see it. It’s really great.

Since the release of Grace, Buckley and his band have been on tour across the globe. Touring as a condition which Buckley finds enjoyable but distracting for writing, or concentrating on anything much at all. Even thinking. “That’s exactly what I did,” he explains. “I spent two years not thinking. I was acting out and I had to think on my feet but in very different ways. It’s a very natural way of being. It was like being a dog.” Playing live and relying on improvisation, however, changed the material and his approach to songs. “It deepened my scope as to the life of a song, from when you make it up and then give it to a band and then take it on the road,” he continues. “It’s elastic by nature. It changes with your every feeling and to be as giving and liquid as your emotions are.”

Buckley has avoided large concert halls in favour of club appearances and small rooms which are more appropriate to his music. “It’s just the conceptual artist in me sees places where I feel like I don’t belong, and places where I do,” he said. “There’s no need to bang my head against the wall so early. Why not go to a place where people who really want to hear it come?

“I’ve never travelled in packs. I’ve always sort of been on the outside. I’ve always been the stranger. Art works better in places where you are allowed to have your deepest eccentricities come out. You need a really good space for that. Sometimes it’s bars, and sometimes it’s like Trinity Church in Toronto. We played in a burrito restaurant the other night. It was amazing.

“I don’t like stadium shows because usually the act on the stage is so big that people take them for granted. In the middle of a song they don’t understand they go away and buy a program, or a hot dog, or a beer, or something. It’s not a musical experience. It’s just like a swap meet, an event. That would kill me. I’d be so sad. Unless you’re like Paul McCartney, and you whip out “Live and Let Die” in a stadium with fireworks, and big screens, and an amazing light show, and a band that knows the songs, and it sounds like exactly a huge, larger-than-life version of it. Or if you write “Hey Jude.” Now you’ve heard that song so long that it totally translates. You’ve heard it so well. But this music you don’t know well at first. It needs attention. But I don’t demand that you sit there and be quiet. Maybe you come to a gig to talk to your friend that you haven’t seen for 16 years, or try to chat up a girl. I’m not about to stop that. It’s fun.”

Buckley’s shows in Sydney reveled in the unexpected, beginning in darkness with a droning sound that became a full-bodied scream by the end. It wasn’t the sheer volume that really had impact, but the sense of a band onstage discovering new things in old songs. That risk of rock & roll band that improvises each night is the possibility of failure and the tension that creates. “It’s hit and miss,” explains Buckley. “Well, that’s the whole point. It could happen, it could not. We don’t know what’s going to go on. That’s the thing, we don’t know what’s going to happen ahead of time. I don’t plan that shit out. It’s pure interaction. I’m leading it, and there might be some text I make up, or text that I’ve amassed over a few days, or sometimes I don’t sing at all. It’s mostly, it’s supposed to be Matty propelling the rhythm with the drums. Lots of reviewers are waiting for this perfect show. But that’s because they have their own expectations all over it. I have no concern for that, or I have no concern for their fear of music. “There’s tons of people that I’ve seen that know the material and come to the show. And the show’s very different. When we made Grace, we were a really new band, and I was just kind of furiously trying to get them together and focused. So after, how many months of touring? About seven months of touring right now, things are completely different. Things are just very evolved not completely radically different. Boys don’t like the music. Men understand the music. Girls like the music.Women like the music. The boys I meet don’t like the music. Like young boys, because that’s who usually show up to punk shows and stuff, or Metallica shows, or whatever. They just sorta…Those are the same guys I’ve known all my life, pretty much. I don’t know. I’ve always been on the fringe. I’ve always been on the fringe of any social thing I’ve been into. I don’t really travel around in packs.”

Perhaps because Jeff Buckley has been saddled with the legacy of comparisons to his late father the singer-songwriter Tim Buckley, who overdosed in the 70’s and whom Buckley never really knew he has been saved from being lumped in with the ‘alternative rock’ hype which has gone berserk.

“I wish it would go berserk,’ he laughs. “I wish it would go insane. I wish it would stop being the middle of the road rock that everybody knows it is. There’s many people that have been totally overlooked. The point of the alternative rock movement is the label-selling point on the label of the so-called music. It’s a fictitious genre. It doesn’t exist.

“What really exists is some post-punk people living in the 90’s who can actually write songs but they just don’t fit anywhere and either they’re an amazing live band or have got themselves on an independent record company. Not because of their sound so much, but probably because of who they know, because it’s very local. It’s not a way of life that you can duplicate just by getting signed to any record company and being called alternative. It’s not like that. People all across the globe have been fooled, I feel.

“I don’t know. I don’t want to be an asshole about it but I wish it would freak me out as much as it promises that it will. But it doesn’t. It’s okay. There’s other things to listen to. There’s tons of stuff Sebadoh, Jon Spencer, Hater, Stereolab, Guided by Voices…There’s all kinds of good things to listen to and they’re current.

“There’s a question as to where I fit into this alternative rock thing. I guess I don’t. I guess I’m not the fratboy’s alternative music of choice. But I don’t know. People show up who want to hear the music. Just be in the moment at the time. At this point people don’t know what to make of me when they come. Unless they’ve got the record. “But ‘alternative music’ - what the hell is that? I know what alternative music is. I could take the Butthole Surfers and clear this room right here. Or I could take Captain Beefheart and make you want to kill me if I stood in front of the stereo and kept you away from it. That’s alternative. Lots of things are lumped into it are very friendly, very poppy. I think Green Day is really easy listening. Billy Joel, Green Day - I could see myself listening to that in the same hour. So I don’t know. I hope everybody comes out of it alive.” Buckley probably will. He is currently back in New York working on a new album and gearing up for his next Australian tour. He’s in no hurry.

“I don’t want to be over-exposed too soon because I’m not… If my music was a cure for cancer, maybe. But it’s not,” he laughs. “It’s just a really individual experience. I’m just glad people like music in general. See, the thing is that I may come out with something I think is the most eloquent thing I can say, and people just won’t get it. It’s totally a crap shoot. OrGrace will hang around and people will see that it’s worthless or people… I don’t know. Music is very strange. Sometimes it hangs around for years, and you hate it, and you think it is the most stinky corpse you can possibly have in your house, and don’t want to see it any more. But one day it creeps in, and you get a moment when you actually need that song. Maybe it’s because of her, or maybe it’s because of him, maybe it’s because of what you need, or somebody dying. That’s the way music is. It’s not like Sega. You get it, and it either works and excites you, or it doesn’t. “While I’m happy about the accolades, and about my acceptance, or any liking of the music, it needs an ongoing dialogue.” Then again, there is the opinion of Captain Beefheart guitarist Gary Lucas, who briefly employed Buckley to co-write “Mojo Pin” and the title track of Grace with him. When asked about Buckley, he remarked, “If they make him Elvis Presley, fine he can handle it.”

©1996 Juice Magazine. All rights reserved